After the publication of the second opening book I co-authored with Jacob, there is one question that I hear more often again and again: “How can I remember all that theory?” I always thought that this is a serious question, albeit one that has a very simple answer: read and practise!

“Remembering” chess opening theory at a good level is something that means different things for different players. For example, my ambitious 11-year-old student who is preparing to get one of the top 3 places in the Greek youth championships in June has never had a chance until now to reach this position that is part of his preparation with White:

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 Nc6 3.Bb5 a6 4.Ba4 Nf6 5.0–0 Be7 6.Re1 b5 7.Bb3 0–0 8.h3!

So, for him it makes no sense to memorize and try to understand more than 1-2 variations 3-4 moves deep starting from this position. To be honest I am not sure how many players bellow 2200-2300 need to memorize more than that. On the other hand, if you are Anand and have to face Aronian in the first round of the Candidates tournament, then it is essential to remember variations far beyond the known tournament praxis. I suppose that most of the readers of this blog belong to the first category, so the methods and ideas I am going to describe are useful only for them. I am sorry Vishy, maybe I’ll do another blog post later for guys like you!

So, after this first observation,

my advice is to give more attention to how “wide” your knowledge is and then try to add more “depth” to it using a lot of practice games at the internet and club.

I’ll first present one of my favourite methods to do the second thing, to get a bit deeper from the level of your existing chess knowledge in a fun way. Then I’ll try to talk about the first step, how to build your first foundations. So, I’ll begin with the “practise” (because it is easier and more pleasant!) and then I’ll go to the “read” of my original answer to the fundamental question I presented at the start of this post.

Getting practical experience in serious tournament games for a new opening is a good way to lose a lot of Elo points, so my advice is to play a lot of blitz and rapid games against humans whenever you find them, either on the internet of at your local chess club. Longer times control games are good as well, but at this stage you mainly need to play just a lot of games to train your intuition about this certain opening. Use this practice to create an “interesting positions database” with lines that you misplayed horribly and have to get better at, positions that you meet again and again and so it makes more sense for you to specialize in them (remember theory a bit deeper that other lines), or lines that you found a nice idea you are proud of and you think that you have to remember the idea for future use. This database must be filtered from time to time so that is not too big and can be scanned quickly before an important game.

In this process, the opening book can be used as a reference that shows what is supposed to be the best continuations for both colours and so a bit of that content should get into that database as well.

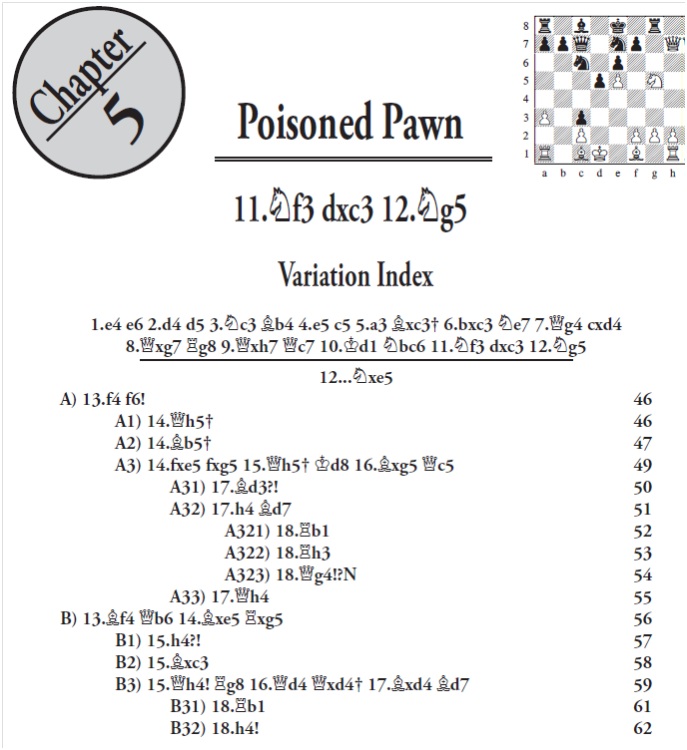

So, let’s go to the beginning. How do we start our work? In every QC opening book there is a starting page for each chapter like this one:

This comes from Grandmaster Repertoire 15 – The French Defence by GM Berg. In this chapter the main line Euwe’s variation (10.Kd1!? and 12.Ng5) is discussed in great detail and you cannot hope to play the Poisoned Pawn of the French Winawer without having at least an idea of how to meet this move. Maybe for my 11-year old student it suffices to remember the line 10.Kd1 Nbc6 11.Nf3 dxc3 12.Ng5 Nxe5 13.f4 f6 and 13.Bf4 Qb6, although he should definitely have a good pass at the critical lines like the B3) and B32) not with the idea to remember them at this point, but to get a feeling how the game might progress. For the rest of us the above tree of variations can be pruned a bit and for example make a pgn with only the continuations A3) and B3) and in that pgn not many more moves that the ones presented in this outline should be added. If a line is forced and the author makes it clear that Black should remember a special idea, then obviously this is something we have to push hard our memory to record, so this goes into that pgn as well.

So, the first step is to create a pgn which contains no more than the above outlines for all the chapters and then, after a pass of the book prune some lines that we think are not essential and add only a few moves to each sub-variation. After this, we have a “wide” opening tree, but not so wide to cover the whole opening, only the most popular lines and it is of limited depth as our first goal is to remember most of these “essential” lines a few moves deep, before we go and practise our knowledge. After our practice we’ll realize what lines we should study deeper from the book or in which lines we can deviate from that, but again each time only a few more moves should be added to that file, because it is the file that we should work hard on to remember each move it contains.

Some lines from the book show how to refute bad tries for the other colour. You can choose either to put those lines into your database of the opening as well, but I prefer to leave this aside and only put these kind of refutations to the other database of “interesting positions”.

Another method which is quite fun and adds a lot of training value to our game, is to make an “opening book” of a few of these “bad tries” and practise them against a strong computer. For example, I made an opening book for Komodo TCEC which contained the B1) line from the above chapter of GM Rep 15 and played a 5 minute game against it. This is what happened:

15…Qxf2

I didn’t read the book recommendation, but as this is a supposedly bad line it shouldn’t be that hard to find the refutation over the board, or at least I have to train to be able to do that in a real game regardless of the opponent sitting across me.

16.Bxc3 Rg8

Not a bad move (I was afraid of a queen check on the back rank), but this is not what Berg recommends. The correct idea is to put this rook at g4 and after that Black is better. With the rook at g8 there is the idea to play a check at b5, put the white rook at f1, take f7 and play the bishop to f6 after which this rook at g8 will be hanging.

17.Bb5+ Kd8

I was dreaming about finding safety for my king at the queenside, but the scary giant lizard found a way to stop me doing that.

18.Rf1 Qc5 19.Bf6 Qxb5 20.Bxe7+ Kc7

20…Kxe7 21.Rxf7+ is not good for Black

21.Rf3

Of course not 21.Qxg8 Qxf1+.

21…Rxg2 22.Rc3+ Kd7

I will not blunder into a checkmate this time with 22…Kb8 23.Bd6#

23.Qxf7 Rg1+ 24.Kd2 Rg2+

24…Rxa1?? 25.Bg5+ and mate next.

I escaped the poisonous bite of the beast with a perpetual, or maybe the beast escaped from my much better position? Probably both, but the thing to get from this is that I am going to remember this …Rg4 now much easier than if I had only read it in the book and at the same time I had a training game with such a strong opponent!

(Nikos and a real Komodo Dragon)

“Next time you’ll not survive you nasty lizard!”

I cannot really say if this “read and practise” method is the best around, but what I can say is that it is easy to implement, it involves active training in the process and not only passive memorization and with it you can find a good way to tame and use the bloodthirsty beasts like Rybka, Komodo and Houdini that are lying around inside your PC.

Nikos

It is one of the best simple (to implement) and practical suggestion – related to “memorizing” opening theory as i have EVER read! It is just 2-3 pages long, but you did it in a great way! I love such an approach and I really love it! I knew there MUST be a better way than simply memorizing theory – the same way… like a machine! Thank you very much and I am looking forward to next parts (suggestions) of this type! 🙂

Thank you Νικος for better directions on how to handle theory and the GM Repertoire books–I often found that I might be in serious trouble in tournament play if I could memorise those 30+ move lines that often cannot be found by just intuitive thinking in a game (at least I could not do so), but it is good to know that just knowing the first few moves of some variations in the tree suffices at levels that are not exactly low, but not top echelon (I range between 2250 to 2350). Like for example, in the 6. Ne5 chapters with the long variations in 11…Qc7 of GM17, I studied the lines and memorised many thereof to the move numbers given in the book, but now I think that I forgot many. At least at my level this would not cause me to lose outright immediately (usually).

I agree this is very practical and useful advice! I have been struggling with the ‘memorisation issue’ as well and will definitely make a second database (next to the ‘complete’ one) with just the essential moves.

Are you guys not missing a sales opportunity? Supplement knowledge above by looking at Forward Chess App on train etc!

In all seriousness, I think the above is very useful – esp on second databases. In theory I would prefer to play computer to practise – I managed to ween myself off my addiction to online blitz 10 years ago and have no intention of breaking my “cold turkey”. In practice, I tend to just wing it at tournaments.

The other thing I’ve noted is it is easier for me to remember lines which I looked at at a teenager 20 years ago, rather than things 2 weeks ago…….

The thing I’m afraid of with this method is that it’ll turn out that knowing the Variation Index is more or less enough — and then why did I just buy the book 🙂 (I know, to get the feel of how to play the variation, and because the index won’t turn out to be enough after all)

I think this is very workable, too. I’m 2000-ish and this is a lot more doable than what’s described in Pump Up Your Rating (which basically advocates immediately building your own theory on top of the book), inspiring as that is.

It’s great that you wrote this — months ago I mentioned to Jacob that I’d like to see “how to work with opening books” on the training blog, and now he’s on holiday at a chess tournament, he has a second, and he has the second write that blog post. Great 🙂

I’d like to thank everybody for the positiove reaction to my article.

@Remco G

The book can be used as a reference tool. Many times what happens to many of us is to play an andgame and after misplaying it in practice we go to an encyclopedia or our endgame book and see how we should have played instead. The same can happen here. You start by studying the whole book without giving a lot of attention in details or at memorising its content. You start by trying to memorise the indexes instead. Then, with the “practise method” you go stp by step deeper in the book, for example examine the whole line if it happens to one of your games, but again not with the intention to remember the whole line, but a bit more than the last time.

With continuous practice and read, you’ll come at a point where you remember quite a lot but most importantly, you have played already (and have lots of experience) a big part of the book. At least this has worked quite well for some people and i’d like to know how this will work for you!

@Nikos Ntirlis

I’d like to add the suggestion that maybe next to the general memorisation (width over depth) one would want to memorise one or two variations in more depth when preparing for a specific opponent. But the nice thing of combining this with improved general knowledge is that you’re not thrown too much off guard if your opponent refuses to co-operate with your preparation (as so often happens to me).

I actually think most people do “just play it and look up what the actual theory is after the game” most of the time, and so they learn from the book little by little. I think you advocate knowing a little bit before the first serious game already, and to play practice games. I need to play practice games against computers more, in my silly online games the lines I need to practice never show up, I play with very little concentration online so I have very weak results and get very weak opponents there.

My practical problem is always with the PGN files. I just can’t keep them organized. Now as well I’m motivated to take an opening book I bought recently and to start some files, but they will become a mess (I add too many moves, or a lot of moves in the first variation and never any in the second) and then I never get around to all the other openings and the next time I want to do something like this I start all over again with a new system… And I end up with many directories with a few random PGN files with some lines in them.

@Remco G

So, start by making a pgn with every game being one chapter (again, i am using as an example the GM Rep books) with the moves being only the ones from the index of the chapter. After that you can start axing and adding stuff here and there, but you will not be able to mess everything up because you’ll start on a solid (organised) base.

Hi

Thanks for the very good post.

I have more or less used a similar method since returning to chess some years ago. My challenge was to build a complete rep. quickly so I simply entered the basic index of some quite old/basic rep-books into Chess Opening Wizzard and started drilling them. In some areas I still only have very short variations but then I might have one or two complete reference games entered. Also I have typed into COW which book/chapter/page I can find additional information, e.g. winning chess middlegames by sokolov page xxx, yy, zz on QGD-tartakover with black etc.

I have been expanding slowly ever since but unlike Nicos I do not play against the computer. Instead I have familiarised myself with the structures/expanded the variations by playing games at chess.com with 1-3 days/move. I have played app 200 such games and that gave me an idea if I was able to play the lines well or not.

I do not care much about the homogenity of my repertoir. If I find a specific (side)line fascinating or if there has been a fascinating discussion at chesspub or something I have much deeper knowledge in that area I could do this in a much more rational way but being fascinated is part of the proces for me.

Larsen_fan

Unfortunately memory cannot be treated like a universal property.

Its like trying to teach someone how to dunk not taking into account his height. If he is 1.50 he cannot dunk (unless he has some other superhuman powers)

Memory may be a single word but it does not represent a single data bank in the brain. I am pretty sure (nothing has been really proven) that memories from different type’s of senses are stored in different “data banks” (severe memory problems of peoples have shown indications of that) and in different ways.

Me being dyslectic and having to face a very difficult task of learning things in a much different way than “normal” people have led me to question the whole learning process.

Personally , my subconscious reaction to my problem was trying to find algorithmic ways to answers. Instead of memorizing a solution, i tried to find generic solutions to problems, with few steps that i could actually remember.

Its important to have a tool to measure one’s memory capacity, else you may expect someone to memorize more that he actually can.

You may not be familiar, but dyslectic people cannot actually memorize the multiplication table. They simply cannot. Its not a matter of how much you try. Its brain wiring and its not a matter of how smart one is, because a handicap in memory creates an “evolution” to other parts of your skills.

So before trying to memorize, its best to “know” how much you possibly can.

Chess is the ultimate memory game , and i mean not just openings etc.

Even calculating involves “short time memory”. The ability to store and retrieve information (something like a cache memory). Set up N chessboards and try to find how many you can memorize. The more you can the better you can calculate. Why? Because one critical part of calculation is remembering the end leaves of your tree of calculations. If you see many positions clearly you make better decisions. Your capacity to do that ofcourse can be enhanced by work but your basic capacity is probably a genetic one.

Can you be a GM with average memory. Yes ofcourse. But not if you have all required skills average (long term memory, short term memory, memory retrieval mechanisms).

I know no GM that has all those average. I guess 2/3 should be above average.

All i am saying , is do not get frustrated if you cannot memorize. You may simply cannot.

You might want a 6-pack but your gene’s may think otherwise 🙂

Hello Nikos,

nice article and really a good help. But my main problem is how to configure a computer chess program like fritz, hiarcs and so on to use such a pgn file. Can you please give a step by step description how one can configure those standard programs? at least for me this would be a great help.

thanks and go on with producing good books and posts for quality chess.

Maybe Quality Chess books should have a short essential knowledge section to add to the great typical position diagrams at the start of each chapter. I think that would be a great addition.

I’ve never really got my head round remembering theory. As someone said above most of the long lines I know were learned years ago!

There is a huge gap in the market for a book outlining tips on how to learn an opening using modern technology. Hardly anyone has a coach you know.

@ Mark

There is chesspositiontrainer. It lacks some functionality (at least for my taste, for example mark some positions as training and then play through), but its the best to help you memorize by repeating.

@Kostas:

Thanks for adding useful information to this blog. And the issue you raised up with the different learning needs for different kind of people is very serious and very interesting. Obviously, my “method” presented here is aimed at presenting some ideas for “general use” and lacks scientific background.

The Winawer Poisoned Pawn is mentioned, but what to do about the lines that have extreme levels of memorisation, because the moves are so illogical and insane, sometimes even for computers, like in 12…d4, or the Botwinnik Semi-Slav main lines, or many lines in the Najdorf Poisoned Pawn?

I used to play the Najdorf 7…Qb6, and I remember in 2002 or so, I tried to memorise to move 40 various lines in the 10. f5 line with 15…Be7 where Black basically had an extra piece but had to block an entire grouping of kingside attacks, sometimes the king ending up from g8 walking to b8 or b7 on move 37 or 38. I memorised it like memorising those complex mathematical formulæ that would take too long and most likely too difficult to derive intuitively on exams, but I am unsure if this method is efficient for chess. I was thinking of clearing the memory with only the very long, illogical lines confined to memory, but in certain opening variations, sometimes 10 or 15 lines that can go past move 35 or whatever are very crucial, and even worse, the theory keeps growing longer and longer. For instance, the line in the Najdorf Poisoned Pawn with 10. e5 h6 11. Bh4 Nd5 12. Nxd5 exd5 is extending past move 35 when just several years ago, 11…Nd5 was not even considered serious, if I remember correctly. And how to remember these moves if most thereof are illogical and counterintuitive?

@Gilchrist is a Legend

Very interesting point. My guess is that such lines are impossible to memorise longer-term, even for GMs. I think this is only possibly short-term, when preparing for a specific opponent shortly before the game. So you would have the full width of your reportoire committed to long-term memory in the way Nikos describes, and added to that you can look deeply to specific (usually tactical / complicated) lines in preparation for specific games – but the latter you would need to repeat at each new occasion where you expect this line to appear. Of course by doing it in this way you run the risk of running into home preparation (i.e. your opponent studied something deeply which you haven’t prepared for), but I guess that is just a risk you have to take. Looking at it from your opponent’s side: they are having the same problem. To be honest, the past 5 years I have hardly ever had an opponent who went for a critical / complex / long variation. In over 90% of my serious games knowledge of the first 10 moves was (more than) sufficient.

Obviously sharp lines require more focous on memorisation, but what is the point of trying to remember move #32 when there is a big chance that you’ll forget move #20? First make sure that untill move 20 you have all things covered and them move forward little by little. As Kostas Oreopoulos pointed out above, this is obviously just one way to do it and different things work better or worse for different people (or for different openings). This is just a general guidline. But to be honest various feedback stimulate me to research this topic even further in the future.

Thanks Nikos for an interesting article!

When trying to learn the Tarrasch from GMR 10 I failed miserably both to memorize the variations and also to play the resulting positions. So I tried a new method that actually worked out pretty well, and it involves laying a proper foundation for the memorization:

1. Before starting to learn the actual theory, I would recommend that you first try and create a mental compass for how to play the ensuing middlegames (a “feel” for the positions if you like). This can often be done by reading annotated games from your opening. It might be blasphemy to write it here, but I often find the “starting out” or “move by move” series by Everyman to be good for this purpose.

2. Then it’s time to practice what you’ve learnt. And I feel that this is a very, very, important step to actually understand the problems and possibilities your opening offers.

Preferably one should play some real games with the opening, but if you’re afraid of losing rating – play a friendly game with a fellow chess friend.

Blitz is also okay, but I think you will have to spend some time analyzing the game afterwards to really activate your brain properly.

3. Once you know the basic ideas, middlegame plans and have experienced the opening (thinking for yourself), it will be a lot easier to understand and appreciate the actual move orders the theory advocates.

And as for the actual memorization the method in the article seems like a very promising way to do it!

@ Jimmy

Actually what you are doing is memorizing patterns, like stepping stones, so you can recreate the paths (variations later). That works fine, but you will never memorize details.

You will memorize tactical patterns and strategic motives (which is much less work that memorizing variations

Also based on your memory capacity you can pick variations

For example. You are white and want to find a variation to play against KI.

Compare KI-mardeplata (main line with e5 Nc6) with Samish (f3 Bg5 for example)

The first requires tons of details (and patterns and strategic motives). The later is much simpler. You will find that you react to the same type of maneuvers the same way again and again.

So you might choose a less ambitious variations just because you can navigate yourself easier in the variation mess

By the way, try to play “photoplay” (the one you get a grid of photos and then try to remember the place where same pictures are placed) and see how well you are doing. Its a good “memory benchmark”

@Kostas

You are of course right in that I’m doing pattern memorization. But I believe the by first understanding plans and ideas, I will have an easier time memorizing specific variations since I know why I make a certain move.

As opposed to learning seemingly “random moves” in a long variation

For the actual variation memorization I also find the concept of using “flashcards” very interesting, if rather time consuming

I’ve been cleaning up my opening “PGNs” (they’re actually Scid databases), starting with the anti-sicilians as black.

I now have a clear division between “lines to memorize” and “collected analysis and stuff on interesting lines”, the first needs to be complete but not necessarily deep, the second can be anything, it’s my workbook. I used to have files with lots on analysis (concentrated in very few lines) and that was what I tried to memorize.

And instead of having 1 game per chapter of a book, I decided to create 1 game per line from memory; I already have a repertoire and it’s based on bits and pieces of many different books. New stuff will fit in. I have 22 games for the anti-sicilians now. They’ve got the bare essentials in them and I have them memorized (because I wrote them from memory :-)). It was obvious that there are lines that I know in quite some detail, and others in which I’ve always been improvising, I need more balance.

Now I can take my games from the last years to see where I need to know more, I can make sure that at least the main lines of the books I want to use are in there, and I’m going to select interesting positions to practice. At least I have some increased inspiration to work on my openings now 🙂

I am not sure about practice games against computers, isn’t the fact the y are tactically all seeing encourages a passive approach avoiding complications rather than more agressive continuation which would likely be successful against a human?

The idea is to play against them in much favourable situations. In this way you get the “habit” to get more accurate (rather than relax) to better positions.

By the way, Carlsen allegedly prepared for his Word Championship match by playing a lot of endgames against Houdini and other engines. I played as well countless times and at many time controls against Rybka some of the critical endgames arising in the Tarrasch and were presented in GM Rep 10 in order to be sure that Black can draw even against the best possible opposition.

Nikos – do you have a source for that claim re: Carlsen training in endgames vs the computer?

I am pretty sure that i read it (or saw it, because he has appeared a lot in TV ) in one of his interviews. Maybe someone with a better memory can help us with pointing out exactly the source?

Nikos, I have a question on the database with ‘interesting positions’: do you mean this literally, i.e., just entering positions with nog further moves, or do mean entering positons with some moves after starting for that position or do you mean the whole game, or something else? In case your answer is ‘whatever suits you best’, which of these would you advice? Thanks again for your interesting post!

No, my idea is to enter the full game score so that this helps you during your preparation for the game when scanning the lines fast.

@Nikos Ntirlis

I see, thanks!

Mmmm. My current way to “remember” lines is just to read (not memorize!!) the books and play the lines and see what I remember. Sometimes a lot; sometimes nothing. After having encountered a certain variation I look it up and will study it more. Next time I play the line I notice a big increase in lines I know, how to play the position and stuff to avoid. In a recent tournament I prepared for an opponent, got the variation I had studied in the database. I was happy, I thought I had him and it would be a walk-over. Then my opponent took a long think and played an alternative which I had not analyzed. I started to think, thought even longer than he did, to conclude that all was not so easy. We got an interesting game which he won after I blundered an exchange in a position where I already had invested a piece for an attack.

In another game I decided to just play classical chess in a Bf4 line, 1.d4 Nf6 2.Bf4 d5. (My normal repertoire is 2…. g6). Well. We ended up in some main-line (as I discovered at home) and I played an interesting (but not really sound) pawn sac and won after his Bf4 had become a bad bishop again (using the route f4-g3-f2-e3) and I had a monster bishop at d5.

In another game I again decided to dish my usual repertoire when being faced with a 6.h3 najdorf. I played 6. … e6 (normally I play e5) , just played normal developing moves but ended up in a bad position with less space and no safe spot for my king. I tried to complicate matters but was outplayed by my opponent and I lost.

And now for the conclusion.

A) Even if you know the lines and get a good position, you still need to play well to win.

B) Not knowing the lines can put you in a bad position from which it will be difficult to recover against good opposition.

C) Experience is the best memorization technique. Just play the lines. Maybe you lose the first time; but next time you will make sure you know it inside out.

D) Memorizing more than 40 moves in a Najdorf poisoned pawn (or even more boring) a Berlin Ending seems to me a complete waste of time. It is probable that in the time it takes you to memorize the line perfectly, it gets refuted by someone somewhere. And then you need to memorize an even longer recommendation against that refutation. And if you do some math about the chance that someone who did not memorize it will play that exact line against you, (which will be probably end in an equal position), then you must agree that there are better ways to use your time.

Hello,

I like the index variation displayed in the original post. The one in Quality Chess Book

I would like to create my own repertoire like this.

I’m trying to find a software that can generate this kind of variant index.

Do you know one?

Earlier versions of ChessBase had a repertoire function that would create something a bit like this.

@Lui

And another option is “Chess Position Trainer”.